I rode the bus in elementary school. (Middle school and high school, too, but this is about me in elementary school.) At the end of the day, if the buses were late in arriving, all of the students who rode the bus would be gathered together in a large room and watched over by a couple of teachers. Because putting several dozen elementary schoolers together in a room can get out of hand quickly, the teachers were smart to come up with an activity to keep us focused: trivia. They would break out cards with trivia questions and split us into teams and have us raise our hands to answer questions. It was a lot of fun.

The reason I mention this setting is because it was there that I first learned about Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow.

I was in fifth grade, and the teacher asked the question “what started the Great Chicago Fire?” I didn’t know the answer, but I remember someone else in my class answered “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow!” and got the point for their team. I thought it weird that a cow could start a fire, but I went with it and was summarily indoctrinated into the myth of the cow and the fire. From that point on, when asked “what started the Great Chicago Fire?”, I would know that it was “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow.”

Fifteen years later, I was having a conversation at work with a friend, and for some reason I can’t remember, the Great Chicago Fire came up. And I thought for a moment about waiting for the bus that day, and how odd it was that the answer was a cow, so I went upstairs and grabbed a book about it (I think it was Robert Cromie’s aptly named The Great Chicago Fire). As I recall, within a few pages, the book made it clear that the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow was indeed a fabrication, and that the real cause of the fire was unknown. I mean, there was a bunch of analysis and discussion of likely causes, along with maps and first-hand accounts, but at the end of the day, the book made it pretty clear that it was impossible to say “X started the fire.”

The realization that the cause was unknown was, for me, a revelation. Not because I was particularly invested in the fire or the story of the cow, but because I realized that now, after reading this book, I knew as much about what started the fire as I did when the teacher asked that trivia question in fifth grade. I received information that it was the cow, then received more information that it wasn’t.

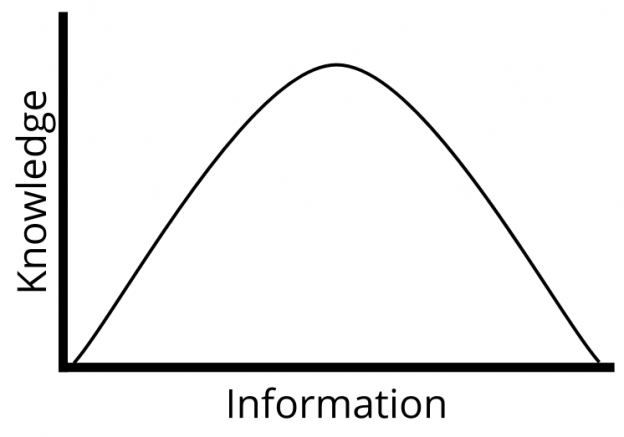

Put another way, my knowledge of the subject could be graphed like a hill: I came in with no knowledge of the cause, then ascended to know it was the cow, then descended to once again have no knowledge of the cause. It was a case of more information leading to no discernible gain in understanding.

I know this is a silly example, but it gets to the core of epistemology and my work as a teaching librarian. A big part of my job is meeting and speaking with students who are new to college, trying to help them feel “at home” within a higher education system that isn’t always welcoming. That often means introducing students to concepts they’ve not previously encountered. And as I do that work, I find that I’m put in a spot where I pitch things as “the truth” when I know them not to be entirely true. Not because I’m purposefully lying to students, but rather, I feel like I should introduce these cultural touchstones, these “myths,” so students have a better understanding of what’s going on. So they feel at least a bit more comfortable at school. In the back of my mind, though, I also know that these myths need to be dismantled. But how? And when?

Here’s a library example…

“Peer-Reviewed Literature.” “Scholarly Sources.” “Academic Discourse”. Whatever you want to call it, a big part of research in the context of higher education relies on this kind of information. Regardless of academic discipline, students will more than likely run into scholarly research on several occasions. What’s more, the vast majority of students have not interacted with this kind of information prior to arriving at college. For that reason, I think it’s my job to help them along with understanding what this research is, how it’s made, and why it’s valued in the academy.

Over the course of those discussions, I have found myself saying things like “this research is written by and for experts within their field…” and “peer-review is meant to guarantee that this research is accurate and reliable…” As a new teacher, I spouted off those lines as a form of mimicry. It’s what I was told as a student, and now I’m passing it along to them. In the last couple of years, though, I’ve come to recognize that I am, instead, perpetuating a myth. I know that peer-review has its flaws. I understand the limitations of academic research. I recognize how slow, and biased, and purposefully inaccessible it is. And yet, I still talk about it with first-year students in a largely positive light.

Why would I do that?

For me, it goes back to the cow. You have to know what the myth is in order to know that it’s wrong. Likewise, I feel like students need to be aware of these concepts, like the reverence for peer-review, before they are in a position to be critical of them. Put another way, they need to learn the rules before they can break them. To catch them in their first year and say outright “these are scholarly sources- they’re just as flawed as everything else…” doesn’t seem to me like it would really be in the students’ best interest.

Still, I struggle with this. When should we broach that subject? I mean, doesn’t it make sense to do it when they’re new to school? Should we really spend time perpetuating myths we know to be false? I’ve often wonder what I’m accomplishing if my desired outcome is for them to learn this thing, then unlearn it. Don’t they still end up at the bottom of the knowledge axis? What’s the point?

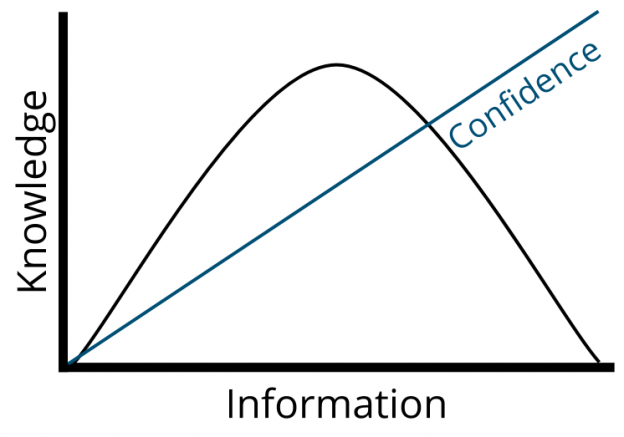

My best guess is that while “more information” does not always equal “more knowledge,” it can lead to “more confidence.” I don’t know what the least biased sources are. I don’t know what the “best” information looks like. But I am confident in my ignorance. I know enough to know that I don’t know what’s right. I do, however, know enough to know what’s wrong.

I suppose that’s at the core of a critical consciousness. We have to have confidence before we can become critical, even if that confidence is tied to our ignorance. I would never want to tell first-year students “by the time you graduate, you won’t know anything more than you do right now,” but I am also fraught with anxiety that that might very well be the case. Information, and learning, are not always tied to knowledge. Moreover, “what we know” is subject to change and revision. Maybe cliches like “the more you learn, the less you know” will take care of that for me?

The real question is, at what point should we try to steer the discussion towards dismantling the myths of “academic research”? Again, I ask, should it be at the beginning? In the case of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow, I didn’t need to wait fifteen years to learn it was a lie, but I feel like I did need to live some more of my life and have some more experiences before I was prepared to say, with confidence, “I have no idea what started the fire…” Mostly because I needed to be ready to follow that declaration with “What started the fire isn’t important. What is important is what happened after that.” Likewise, it isn’t enough for students to be ready to say “Scholarly sources are good or bad sources of information.” They need to be ready to follow that with a “because…” They need to be ready to address all of the reasons that scholarly discourse is still useful, and all of the ways that it’s flawed. But they can only develop that context after they’ve been introduced to it, and applied it, and reflected on those experiences for themselves.

So this is where I am right now: trying to develop a pedagogy to introduce concepts, and hold them in esteem, while at the same time leaving enough room for these concepts to be reduced at a later point. And, while we’re at it, doing so in a way where the students’ won’t look back and ask why I lied to them.

In other words, the more I learn about teaching, the less I know about how to do it.

I love that.